If you can buy a home in the metaverse, why not on the moon? The heavenly body has already hosted visitors, played a key role in earthly geopolitics and may be home to untold mineral treasures. Traffic jams, collisions and debris all point to outer space facing some of the issues that bedevil planet earth. High time, reckons the neoliberal Adam Smith Institute, to consider privatisation.

This is a long shot, to put it mildly. As things stand, the moon — like other celestial bodies — cannot be appropriated by any sovereign or militia, under the Outer Space Treaty it is the “province of all mankind”. Changing that would require international consensus and a mindset shift rather too grand for a world struggling with earthly borders and reappraising globalisation.

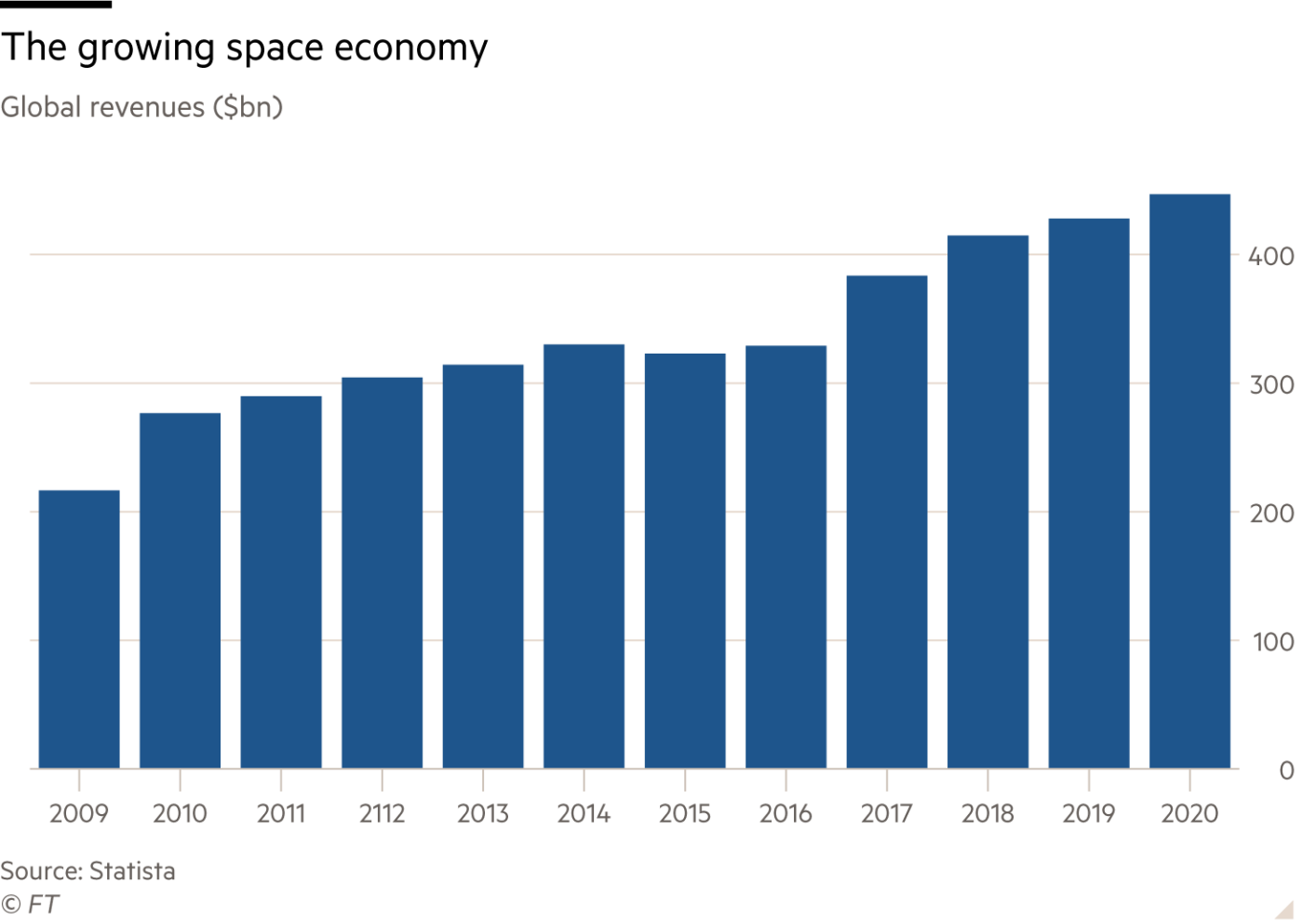

Virtually every country has lunar ambitions but the big muscle comes from the US, Russia and China, an uneasy set of bedfellows at the best of times. Increasingly, space is in the sights of individuals who have amassed earthly wealth: Elon Musk, Amazon’s Jeff Bezos and Virgin founder Richard Branson, among others. That illustrates the shift in motivations, from national pride to financial incentives. The global space economy was worth an estimated £270bn in 2019 and is projected to almost double to £490bn by the end of this decade.

There would be losers too from a carve-up that allotted parcels to the modern equivalent of 16th century colonisers. Imagine a sovereign controlling not just a gas pipeline but entire communications. The UK has estimated that blocked access to global navigation satellite systems for just five days could cost the country £5.2bn. Consider too that the triumvirate of countries leading the way have vastly different ideas about both property and human rights.

Rebecca Lowe, the author of the paper, proposes getting round this with temporary and conditional ownership of plots. Owners, more akin to long term renters, could not hand their plots down from generation to generation.

Because rent cannot be paid to the man in the moon, a philanthropic fund would take the money and redistribute it into areas of common good such as conservation, say, or scientific endeavours.

Plenty of critics see this as about as likely as chunks of moon going on sale at the local fromagerie. But precisely because humanity has made such a hash of carving up the earth, it is a worthwhile debate to start.